|

Sant'Apollinaire Nuovo

|

|

|

|

|

|

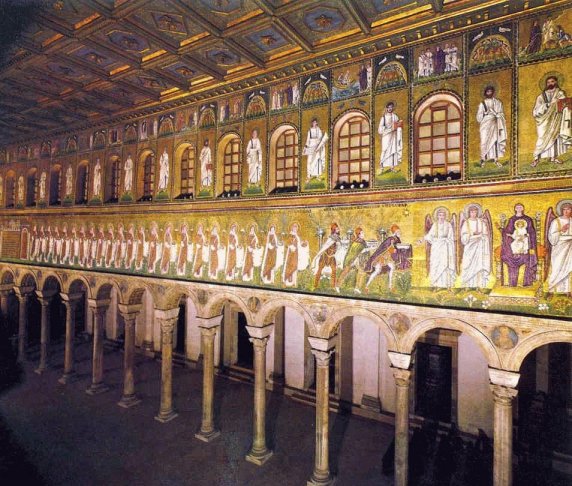

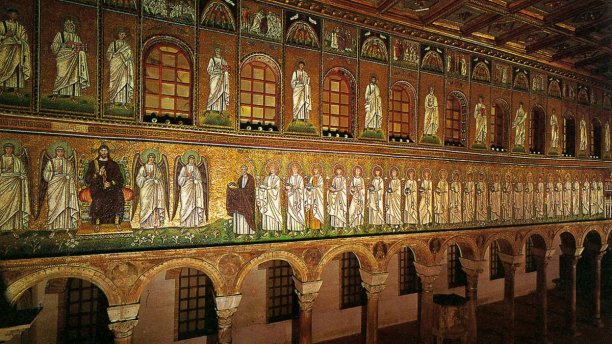

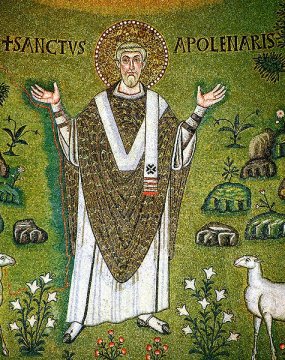

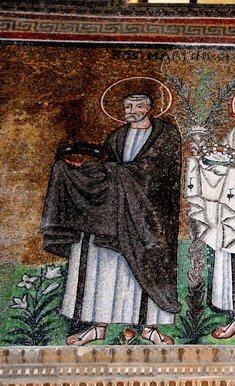

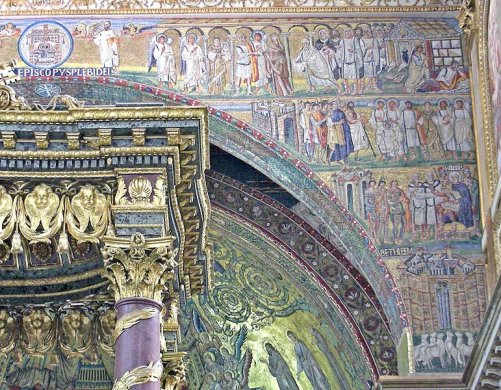

A brief history. Sant'Apollinaire Nuovo was built by Theoderic the Great, and dedicated in 504. Theoderic was King of the Ostragoths, and ruled Italy from 496 to 526. The Ostragoths were Arians rather than Catholics, and this fact has exercised art historians. Sadly, as we shall see, definite conclusions have proved hard to come by. Theoderic was a tolerant ruler, and he had no problem with the Catholic churches in Ravenna. Theoderic's original dedication of the Church was to Christ the Redeemer. After his rule, the somewhat less tolerant Catholic hierarchy suppressed Arianism. The church was reconsecrated in 561 and dedicated to Martin of Tours. This was rather pointed; Martin was dedicated to the destruction of Arianism. The present dedication dates from 856. The relics of St. Apollinaris had rested at S. Apollinaire in Classe outside the city, and thus were vulnerable to attack. They were brought into the city for their protection, and the church was renamed, though 'nuovo' really signifies new resting place for the relics rather than new church, as this church was older than S. Apollinairre in Classe. The church today The church is visited for its wonderful mosaics, many dating from the foundation by Theoderic. They are in three bands. The top band shows scenes from the life of Christ (left wall) and scenes from the Passion (right hand wall). These date from the foundation of the church, though some have been altered and restored over the years. The central band shows various saints and evangelists, alternating with the windows. These too date from the foundation of the church. The lower band date from the reconsecration. The left wall shows a procession of virgin martyrs, basically the same image repeated 22 times. They are lead by everyone's favourite mosaic, the Magi, (top of this page). They are all heading towards a mosaic of the Virgin and Child flanked by angels. The right wall shows 26 male martyrs, lead by St Martin, who wasn't a martyr at all but had to be there for reasons outlined above. Saint Apollinaris is there too, and he was martyred. I've included his mosaic below. I have a particular affection for Apollinaris, patron saint of gout sufferers. The martyrs are heading for a mosaic of Christ surrounded by Angels. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

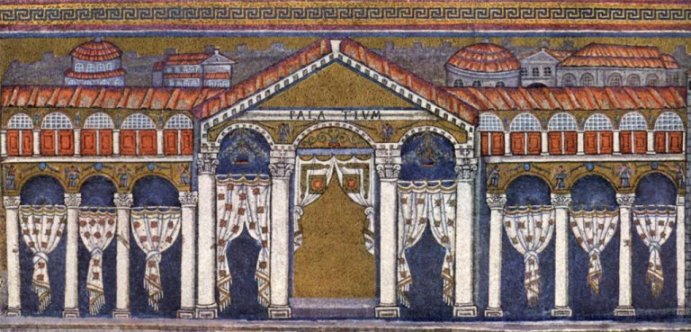

The western end of these lower bands are

interesting. They date from Theoderic's time. The left hand

wall shows the port of Classis complete with ships. The right hand wall

shows Theoderic's palace. Originally the parts showing curtains had

important figures from Theoderic's time, including, perhaps, Theoderic

himself. The new bishop of Ravenna couldn't be doing with this, and

so the figures were replaced with the curtains. An arm from one of the

figures remains on a pillar. These mosaics beg a few questions. Was this band originally completed in Theoderic's time, but removed by the Catholic bishop? If so, what did they show? The two remaining mosaics suggest secular rather than sacred themes, and certainly disposing of images of Theoderic as king was as important as getting rid of images showing aspects of theology that the Catholic church would have disapproved of. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The original mosaics in the top band are

probably the most interesting, so let's look at them. As I've mentioned

above, art historians spend much time on these, and, would you believe,

they don't agree with each other. Here's André 'These mosaic scenes do not correspond at all to ones ideas of narrative imagery, because instead of being precise and detailed they show only a minimum of detail - only what is strictly necessary to make the subject recognisable. . . . Aside from several expressive heads, this art is still on the level of cliché: and the images, in the last analysis, are not very different from the image-signs of the catacombs . . . No wonder that these panels were relegated to the top of the walls, since nothing would have been added by having them closer to the spectator.' Giuseppe Bovini, in the standard guide book, Ravenna, art and history, doesn't agree. 'The mosaics of Theoderic's time' he tells us, 'present figures with forceful outline, but especially in the small panels above, they show a certain freedom of movement, together with a spontaneity and animation which are at times surprising.' We'd better have a look at one or two. The first two are from the left hand wall, the second two show scenes from the Passion. (Right hand wall.) |

|

|

|

|

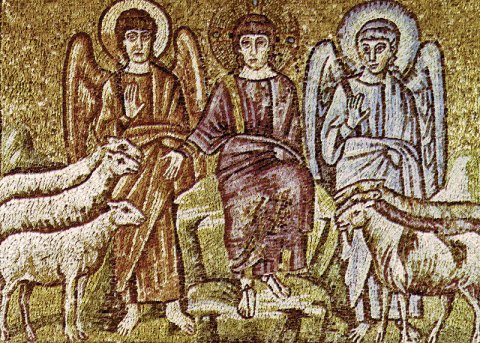

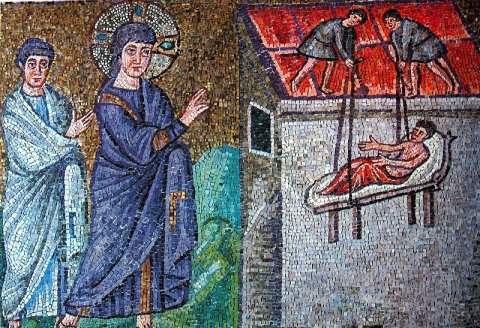

| Dividing the sheep and the goats The cure at Capernaum of the Paralytic | |

|

|

|

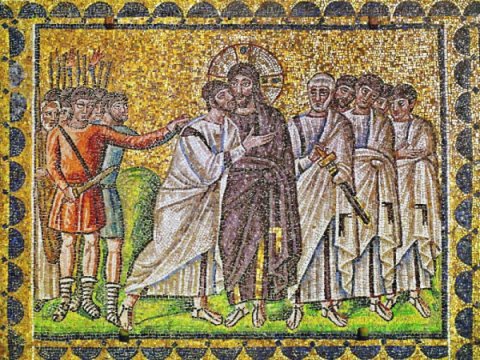

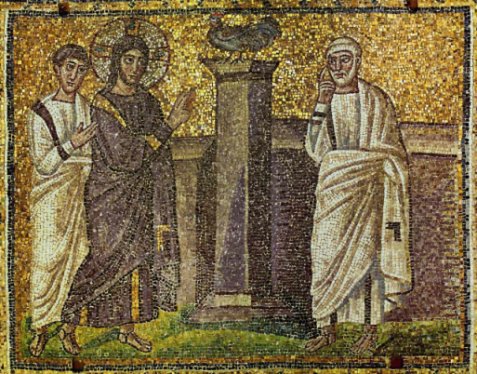

| Betrayal by Judas Jesus tells Peter he will deny him | |

|

Note that in the scenes from the life Christ is beardless, while in the passion scenes he is bearded and looks older. In the scene of dividing the sheep and goats it is claimed (by some) that the blue figure is Satan, the first depiction in art, as, at the time, blue was (supposedly) considered a sinister colour. (Those that propose this seem to not have noticed the colour of Christ's robe in the healing at Capernaum mosaic.) To my eyes, he looks a rather more friendly character than the angel on the other side. Now to the tricky business of Arianism versus Catholic orthodoxy. Theologians of the period argued endlessly about the nature of Christ's divinity. Was he divine, or human, or some of each, and how did that work? Was he equal with God, as one of the Trinity, or subservient to God? The Arian view was that Christ was created by God for a specific purpose - the redemption of mankind - and thus was subservient to him. Arianism was a Unitarian faith. (Note: for elucidation on the complexities of early Christianity I always turn to Diarmid MacCullouch's excellent A History of Christianity.) The question then arises - how did this affect the art produced by and for Arians? A number of academics have attempted to address this, most often in relation to Sant' Apollinaire Nuovo as there is little else to go on. Much of the evidence for Arianism here seems to be based on what is not there rather than what is. It is pointed out that selection of scenes from the Life of Christ is rather odd. Key moments, particularly the Annunciation, Nativity and Baptism, are missing. The Passion scenes do not include the Crucifixion. Could the omission of scenes that suggest Christ as a God-like figure be evidence of an Arian agenda? Likewise the beard; is has been suggested that the suggestion of Christ aging through the cycle stresses his humanity. Robin Margaret Jenson in Understanding Early Christian Art, is sceptical of these ideas. Yes, Passion images of Christ frequently show him bearded, but not always. In any case, were these mosaics overtly Arian they would have been removed. Arians did have images of the baptism; we will come back to them (and to beards) when we look at the Baptisteries. Jensen reminds us that what is being forgotten here is the early sixth century context, and the sources from which these images were drawn. In this respect, I think André The image of the Magi shows, however, that the there was an awareness of the missing scenes after the reconsecration. While the baptism could be safely left to the baptisteries, and the crucifixion was an image still shied away from, an image suggesting the Incarnation needed to be there, and the Magi image is the best demonstration of Christ's divinity. It is interesting, however, to compare Sant'Apollinaire Nuovo with the mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, the earliest of which are nearly a century older than the ones in Ravenna. Clearly these are from the Catholic heartland and stress the divinity of Christ in no uncertain terms. Perhaps the answer is the mosaics in Ravenna, perhaps by Byzantine mosaicists, weren't overtly Arian, but looked back to an earlier time; the image of the Good Shepherd in the Mausoleum of Galla Placida is another example. |

|

|

|

|

| A conclusion reached then? As usual, not quite. So far, I have ignored the most controversial image at Sant'Apollinaire: I'll discuss it on the next page. | |