|

Pisa |

|

| A busy Italian

city, with a wonderful cluster of buildings at its heart. This area is

known these days as the Piazza dei Miracoli, but this is a twentieth

century invention. The Bonechi guide to Pisa firmly tells us

that this term is incorrect, then continues to use it throughout the

book! I will be correct (if pedantic) and call it the Piazza del Duomo. On our visit in September 2012 we took the train from Florence - an easy journey, but the station is the wrong side of town for the Duomo and it is tempting to jump on a bus or get a taxi. My suggestion is - if you arrive by train, enjoy the walk through the city, and come back by bus or taxi - after exploring everything that is to see at the Piazza, you will be pretty weary! One thing you will miss if you don't walk is the beautiful Santa Maria della Spina, which owes its spiky appearance to once having a thorn from the crown of thorns. |

|

|

|

|

| Sadly this

little church breaks the rules I have set myself for art in context -

the church isn't in its original location - the building was moved here

in 1871 to avoid flooding. The thorn has gone too, to another church in Pisa. So let's

cross the bridge and head for the Piazza del Duomo. |

|

|

|

|

| The main attraction is, inevitably, the leaning tower, so if you really must have a photograph of yourself pretending to hold it up get that out of the way first - better still, don't bother; head straight for the baptistery and my first 'art in context'. | |

|

|

|

|

Nicola Pisano: Pulpit, Baptistery, Pisa |

|

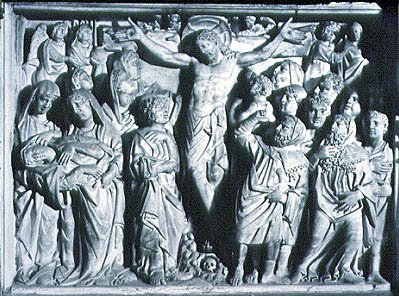

| Nicola Pisano's pulpit dates from around 1260. There's lot to be said about this, but I am going to focus on the five carved panels showing scenes from the life of Christ. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A few yards from

the baptistery is the Campo Santo; we'll be heading there to look at the

frescos on the next

page. For now we'll look at a couple of the sarcophagi on display there.

These first century sarcophagi were originally placed around the walls of the Duomo, being reused for Christian burials. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| That Pisano used these classical sarcophagi as models is self evident. |

|

|

|

|

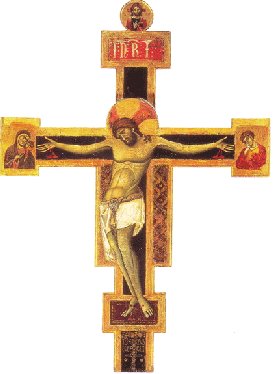

| This suggests that Pisano was rather backward looking; the opposite is in fact the case. The appreciation of classical sculpture is often seen as a product of the Renaissance; it started rather earlier than that. Before coming to Pisa, Pisano worked for the colourful Emperor Frederick II who, when he wasn't being excommunicated by the Pope, encouraged the study of Classical art - but with a difference. Classical figures showed no emotion, but the mid thirteenth century saw a movement towards far greater feeling in Christian arts. Just look at those faces in the crucifixion scene. An interesting comparison can be made with this crucifix by Giunta Pisano that predates the pulpit by twenty years or so. (No relation - Pisano means 'of Pisa'. It became a family name for Nicola's descendants later.) It comes from a Pisan church - now in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa. This is one of the earliest examples of a 'Christus Patiens' (suffering Christ) crucifix. Look again at the crucifixion scene from the pulpit - did Nicola know this crucifix? |

|

|

|

|

Once you have spent time in the baptistery head for the Duomo and look for another pulpit - and another Pisano! |

|

|

|

|

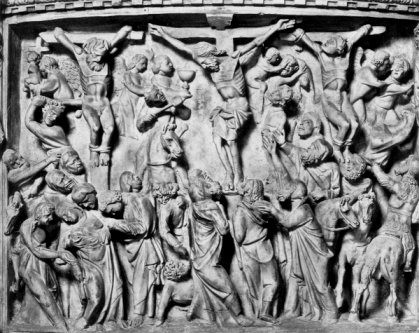

| Giovanni Pisano was the son of Nicola, and his crucifixion scene, c 1302, moves the story on a further stage; the figures are more deeply incised, and the emotional impact of the scene that much greater again. | |