|

Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere, Hampshire |

|

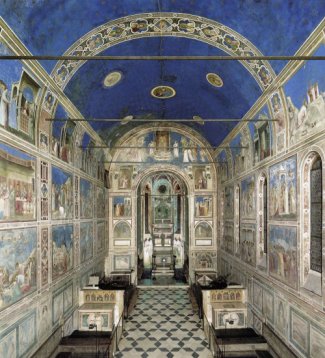

It always amazes me that the Sandham Chapel is not better known. In my view it is the foremost example of 'art-where it-is-meant-to-be' in Britain. The chapel was built in the 1920s as a memorial to a soldier, Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham, who died in the Great War. This in itself makes it unusual; it has not been the British tradition, at least since the Reformation, to dedicate chapels to the dead. Most First World War casualties had to settle for a secular war memorial in their town or village. The chapel was dedicated as the Oratory of All Souls by the Bishop of Guildford in 1927. The chapel was filled between 1926 and 1932 with oil paintings by Stanley Spencer. They are very personal paintings based on Spencer's own wartime experiences; he worked as a hospital orderly. It is often said that the scheme reflected Spencer's interest in the frescos by Giotto in the Scrovegni chapel in Padua, and I'm going to explore that idea. One possible reason for this chapel being rather less well known than the Scrovegni is that the paintings are copyright, and will remain so until 2029. As a writer, I say three cheers for copyright, but with art it means that images are more difficult to come by on the Internet. Some might say that another reason is that the Scrovegni is immeasurably greater than Sandham, but I'm not interested in value judgements - it's not what this website is about, though there's no doubting the importance of Giotto's work in the history and development of art. Visitors to the two venues will have to make up their own minds about which they prefer. Looking at the outside view of the two chapels is interesting. Both are simple brick buildings that give no inkling of what you see when you walk through the door. |

|

|

|

|

|

Scrovegni chapel |

|

|

|

|

|

Sandham Memorial chapel |

|

| Inside, though, difference is all. Giotto painted subjects very familiar in religious art: the life of the Virgin, the life and Passion of Christ, the last Judgment. Spencer's subjects include scrubbing the floor, sorting laundry, filling tea urns, bed making, and having tea. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| So, in

medieval Italy, we have a Crucifixion; in twentieth century England, we

have people cleaning their teeth and making beds. We really need to look at the differing function of these two buildings. Both were built with a deceased person in mind. The Scrovegni chapel was built by Enrico Scrovegni for his father, Reginaldo degli Scrovegni, a notorious userer. We meet Reginaldo in Dante's Divine Comedy, where he suffers in Hell alongside the damned sodomites. Aware of where his father would most likely be, the dutiful Enrico built the chapel in hopes that the Virgin, to whom the chapel was dedicated, would intercede on poor old Reg's behalf. (She didn't, according to Dante.) At least spending all that money might do Enrico himself a favour. This is sounding like the mindset of a twentieth century agnostic here. Certainly the whole notion may sound ludicrous to modern ears, but it didn't then. In 1300 it was deadly serious. I don't know the precise motivation of Lieutenant Sandham's sister and brother-in-law in commissioning the chapel, but it was certainly miles away from the thoughts of Enrico Scrovegni. The truth must lie in the name - a memorial chapel, built so that a loved person would not be forgotten. And this idea informed Spencer's paintings - his memories of the war, some trivial, some less so. I think there is another consideration that places the Sandham paintings firmly in their English context. Rather like the humorous gargoyles on medieval churches, and the image of the gossiping women and the devils on the preceding page, the British have never been prepared to be overawed by holiness. And yet . . . Let's do another comparison between Spencer and Giotto. |

|

|

|

|

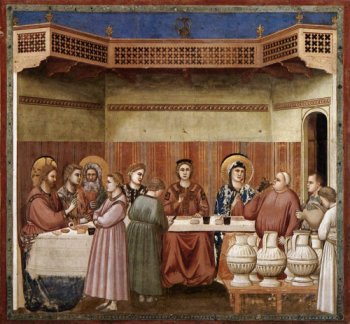

| It's true that

making jam sandwiches doesn't quite rank with turning water into

wine, but look at that portly steward in Giotto's fresco tasting

the wine in some astonishment. I don't think that Giotto was entirely overawed either. Finally, lets look at the only painting in the Sandham chapel that can truly be described as religious, and the Giotto equivalent. |

|

|

|

|

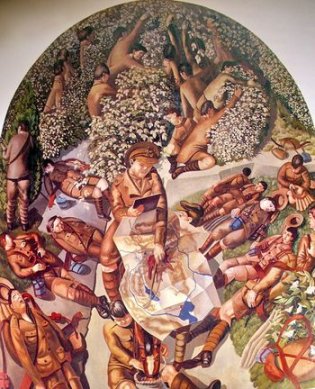

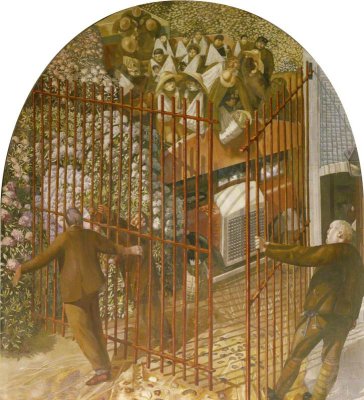

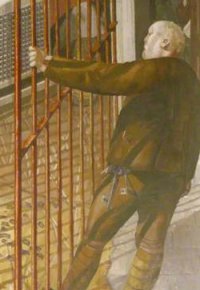

| Neither

painting works that well at the size I can show them here. In

particular, the Spencer is quite hard to make out - you'll just have to

head to Burghclere for a better look. We see the dead soldiers emerging from the graves and handing over their crosses to Christ, which is in the middle distance and not easy to see. Even the dead donkeys and ponies have been resurrected. Now alive once more, the soldiers are busy sorting out their kit. Resurrection, but no judgment. The soldiers have all done their bit, and are worthy of salvation, unlike the poor losers on Christ's left in Giotto's painting. The soldier's situation may not look that heavenly, and their tasks rather more mundane than those that await the saved in the Scrovegni chapel - but that's British understatement for you. Footnote: Sandham revisited, July 2013 Another visit, and a realisation that my comment above, about the secular nature of most of the pictures, is wrong. Many, if not all of the pictures have a concealed religious reference. This may be as simple as a figure with his arms stretched out to form a cross. The picture below shows a hospital gate being opened to allow in a troop-carrier carrying the injured. The figure opening the gate is modelled on Spencer's least favourite sergeant-major. But look closely at that bunch of keys. Isn't this St. Peter, opening a rather different gate? The keys are actually those to Sandham Chapel, and are still there. The kindly guide took them out of a drawer for us to see. |

|

|

|

|